Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907)

The Nichols House Museum collection includes three bronze works by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a close relative of the Nichols family and one of the most important sculptors in American art history. During the three decades of Saint-Gaudens’s career, he completely altered the medium by supplanting a tired Italian Neoclassical aesthetic with a naturalistic French-inspired style [1]. Instead of using marble, which was predominately used in nineteenth-century sculpture up to that point, Saint-Gaudens’s work championed bronze. Bronze not only suited Saint-Gaudens’s lively technique but it also represented American innovation, and it became central to the ethos of his work [2].

Augustus Saint-Gaudens was born in Dublin, Ireland to a French father and Irish mother. Six months after his birth, his family emigrated to New York in order to escape the Irish potato famine. Saint-Gaudens was first apprenticed to a French cameo cutter at age thirteen and continued to apprentice in that trade until he departed for Paris in 1867. Saint-Gaudens was one of the first American sculptors to opt to train in Paris rather than Florence or Rome. He preferred Paris for its burgeoning modernity and the coinciding Exposition Universelle, the most recent in a series of world’s fairs that established Paris as the cultural capital of the world. In 1868, Saint-Gaudens was formally admitted to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts which emphasized the realistic treatment of the human form and bold expression. However, in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War interrupted his studies and he relocated to Rome, finding company in other American expatriate sculptors such as William Wetmore Story, William Henry Rinehart, and Harriet Hosmer [3]. There, in 1872, he completed his first major work, Hiawatha, inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow‘s hugely popular lyric poem, The Song of Hiawatha, first published in 1855. In December 1873, Saint-Gaudens met Augusta Homer (1848-1926), sister of Elizabeth Nichols, who was also studying art in Rome. The couple was engaged later that spring but did not get married until 1877, after Saint-Gaudens had secured the commission for the Farragut Monument. The Monument was the most sought-after commission at that time and demonstrated to Augusta’s parents that Saint-Gaudens’s art career could support a wife. In 1880, their only child Homer was born, at which point the family settled in New York.

Saint-Gaudens’s outgoing and charismatic personality aided his career and enabled him to develop friendships with fellow creatives. His brother Louis, also a sculptor, observed that Saint-Gaudens could “curry favor with the rich like a flunkey” [4]. Perhaps his most famous friendship was with the celebrity artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). They greatly admired each other’s talent and exchanged artwork over their decades-long friendship. In a letter to his niece, Rose Nichols, Saint-Gaudens described Sargent as, “…a big fellow and, what is, I’m inclined to think, a great deal more, a good fellow” [5].

Saint-Gaudens vacationed in Cornish, New Hampshire, for the first time in the summer of 1885. An Arcadian farming town on the Vermont border that overlooks the Connecticut River, Cornish offers incredible views of nearby Mount Ascutney and was thought comparable to the Italian countryside by Saint-Gaudens and his Cornish neighbors. Saint-Gaudens returned to Cornish each summer between 1885 and 1887 with his family and studio assistants, who likewise found Cornish an inspirational setting for creating work. In 1891, with his career firmly established, Saint-Gaudens purchased a Greek Revival farmhouse which he renamed “Aspet” after the town in the French Pyrenees where his father was born. Today, the site is maintained and interpreted by the National Park Service.

A group of artists began to coalesce around “the God-like sculptor” in Cornish and they came to be known as the Cornish Art Colony. The Colony included painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, actors and other creatives. Painters Thomas Wilmer Dewing, George de Forest Brush, and Maxfield Parrish were prominent Colony members, as were fellow sculptors Herbert Adams and, for a brief period, Daniel Chester French and Paul Manship. Architect Charles Platt established a Cornish residence as did writer Winston Churchill, whose Harlakenden House was made a White House summer residence by President Woodrow Wilson. In 1892, Rose Nichols, then 20-years old, persuaded her parents to purchase property near the Colony which they renamed “Mastlands.” Rose was Saint-Gaudens’s favorite niece and she, in turn, idolized her uncle for his genius. It was at Cornish that the Saint-Gaudens and Nichols families grew especially close.

Although Saint-Gaudens was at ease among high society and fellow artists, he was not prone to deference. Still, he found himself enthralled by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) who was at the center of celebrity culture in the 1880s [6]. In his Reminiscences, Saint-Gaudens wrote, “I am, unfortunately, not much of a reader but my introduction to [Stevenson’s] stories set me aflame as have few things in literature.” Saint-Gaudens reached out to Stevenson through a mutual friend, the American painter Will H. Low, and offered to model Stevenson’s portrait should the writer travel to the United States [7]. In 1887, Saint-Gaudens had his opportunity and after multiple sittings in both New York and New Jersey, he completed his portrait of Stevenson which became his most commercially successful relief despite receiving mixed reviews from critics. The portrait depicts Stevenson, who suffered from tuberculosis, reclining in bed with a pen in hand (a cigarette in early versions) and a stack of his papers in his lap. In the upper left corner is an excerpt from a poem by Stevenson, To Will H. Low — Youth Now Flees, thus memorializing the friendship between the three men. Additionally, the poem, which was published in Stevenson’s 1887 poetry collection, Underwoods, relates to mortality and the fleeting nature of life, and its inclusion reinforces the portrait’s functions as a “future memorial to the ailing author” [8]. This intimate portrayal of Stevenson is in stark contrast to Saint-Gaudens’s hypermasculine Civil War memorials. The portrait in the Nichols House Museum collection (1961.127) is a singular cast dedicated to the artist’s niece. The dedication, “To Rose Standish Nichols / Augustus Saint-Gaudens” appears in the upper right corner. It was produced in the late 1890s after Saint-Gaudens began copyrighting his works for the commercial market. The frame is original.

In 1887, the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White received a commission for a new Madison Square Garden in New York. Saint-Gaudens, a close friend of the architects, was asked to produce the finial for a thirty-two-story tower with a weathervane based on Giralda Tower in Seville. In 1891, an initial version of Diana the Huntress was installed at the top of the tower, Saint-Gaudens’s first and only female nude. This first version, made of hammered and gilded sheet copper over a steel armature, stood eighteen-feet tall and was deemed disproportionately large for the tower. Furthermore, the statue couldn’t perform the function of a weathervane due to its weight. It was replaced in 1893 by a thirteen-foot second version which, despite some controversy surrounding the nude figure, was a great success. Diana remained at Madison Square Garden until 1925 when the arena was demolished (this version is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the original was destroyed sometime after 1909).

In the mid-1890s, Saint-Gaudens began casting his more iconic works for the commercial market, which proved extremely lucrative. In 1895 he copyrighted Diana and cast a number of reduced versions. The version in the Nichols House Museum collection (T-59) is the rarest of these types: a 21-inch figure balancing atop a full orb (rather than a half-orb) on a two-tiered base with an early date of 1894. At one point, Rose Nichols quipped that if all she received in life were a Robert Louis Stevenson and a Diana, she would be happy.

A final piece of sculpture by Saint-Gaudens in the Nichols House Museum collection is Head of Victory, derived from a study for his Sherman Monument in Grand Army Plaza in New York City. Completed in 1903, the Sherman Monument depicts General Tecumseh Sherman led by a winged figure of Victory. American painter Kenyon Cox said of his friend’s Victory figure, “She has a certain fierce wildness of aspect, but her rapt gaze and half-open mouth indicate the seer of visions: peace is ahead and an end of war.” Prominently displayed on the mantle in the parlor of 55 Mout Vernon Street, this early version in the Nichols House Museum collection (1961.173) dates to 1902 and is gilded bronze on a butterscotch marble base. Like the Robert Louis Stevenson portrait in the Museum’s collection, it bears a dedication to the sculptor’s niece: “To Rose.” At his Cornish studio, Saint-Gaudens revised the head of Victory several times while the Sherman Monument was being cast. It is speculated that the figure’s hair was modeled after Rose Nichols’s.

In 1905, the residents of Cornish collaborated to produce “A Masque of ‘Ours’: The Gods and the Golden Bowl” in celebration of Saint-Gaudens’s twenty years at Cornish. The masque, or play, was written by playwright Louis Shipman (husband of garden architect Ellen Biddle Shipman, a colleague of Rose Nichols) and the music was composed by Arthur Whiting. It was performed on a June evening in the field below Aspet. Kenyon Cox played the role of Pluto and Maxfield Parrish the centaur Chiron. Rose Nichols and her sisters were cast as nymphs. Saint-Gaudens was so moved that he created a plaquette inscribed with all the participants’ names (including the Nichols sisters) to commemorate the event. The column temple stage on which the masque was performed was replicated in marble by Kenyon Cox to mark the site of Saint-Gaudens’s grave.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens died in Cornish in 1907 after a seven-year struggle with cancer. National and international newspapers published hagiographic obituaries that declared him the greatest American sculptor. In October 1908, Rose Nichols published her correspondence with her uncle in McLure’s Magazine. Saint-Gaudens played an important if not decisive role in Rose Nichols’s life and his presence is felt throughout the Nichols House Museum.

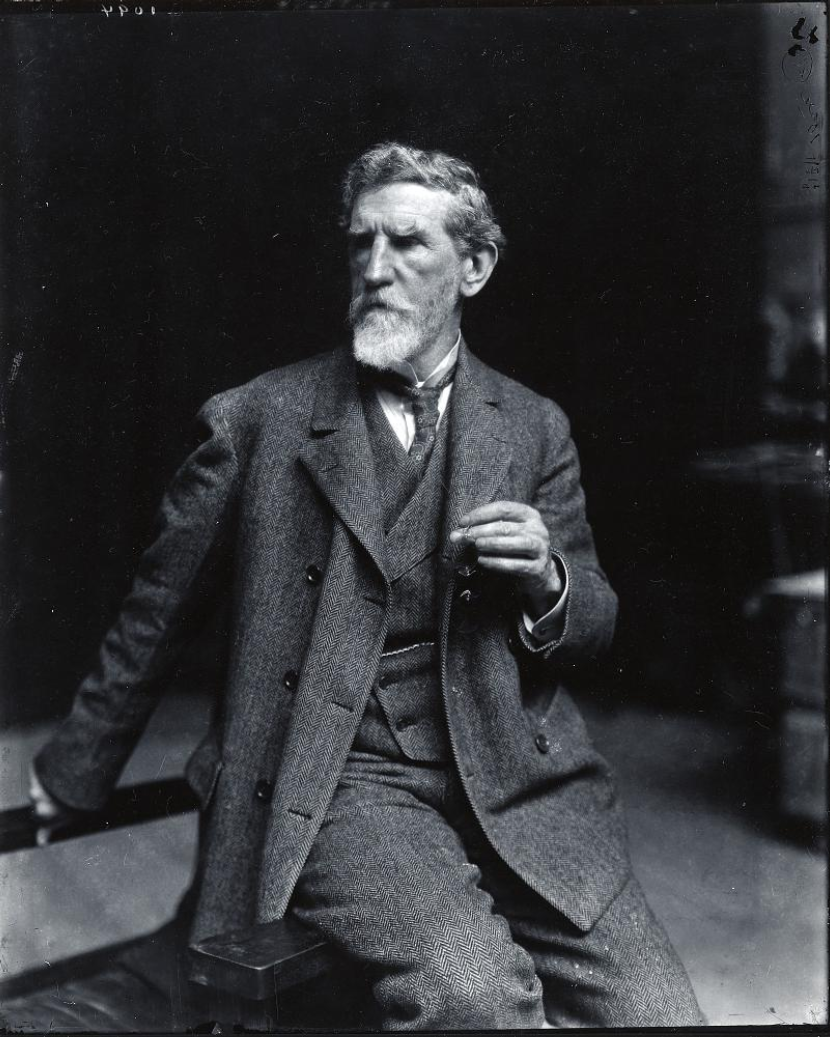

De Witt Ward. Saint-Gaudens in His Studio, 1905. Photograph. Archives and Special Collections, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Peter A. Juley & Son Collection (J0021708).

Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Robert Louis Stevenson, 1887-88 (this cast, ca. 1897). Bronze plaque in oak frame. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.127.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Diana, 1893-94 (this cast, 1894). Bronze. Nichols House Museum collection, T-59.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Head of Victory, 1897-1903 (this cast, 1902). Gilded bronze. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.173.

Kenyon Cox (American, 1856–1919). Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1887, replica 1908. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of friends of the artist, through August F. Jaccaci, 1908. 08.130.

Paul Manship (1885-1966)

Paul Manship (1885-1966) belongs to the generation of American sculptors that succeeded Saint-Gaudens and the Beaux-Arts tradition but whose style was the antecedent of Modernism. Manship visited the Cornish Art Colony in the early 1900s and was no doubt inspired by Saint-Gaudens, however, his approach differed greatly. Manship achieved tremendous success in the interwar years and is the most famous of the Art Deco sculptors. His best-known work is Prometheus, created in 1933 and installed the following year at Rockefeller Plaza in New York.

In 1905, he enrolled at the Art Students League in New York and after a few months became an assistant to the sculptor Solon Borglum, whom he considered an important influence on his work [9]. In 1909 he won a scholarship to study for three years at the American Academy in Rome, which had been founded in 1894 by architect Charles McKim, Saint-Gaudens’s close friend and colleague. While in Rome, Manship fell in love with Greek and Roman antiquity and thereafter his sculpture embraced classicism. He returned to the United States in 1912 and experienced immediate success, selling all ninety-six bronzeworks shown in his first exhibition [10].

During this early stage of his popularity, Manship created two bronze sculptures, Adam and Eve. Only a few copies of these first versions exist, including the pair owned by the Nichols House Museum (1961.344.1, 1961.344.2.) Produced in 1922, these sculptures are highly stylized yet still representational, showing Manship’s preference for clean lines and movement. Manship embraces archaism in his choice of mythological and classically derived themes, as well as his dedication to the simplified form. Art historian Susan Rather argues Manship should be understood as bridging the gap between the academic and the radically modern.

These sculptures likely came into the Nichols House Museum collection as a gift to Rose Nichols by the artist, who she knew from his summers spent at Cornish.

By the 1940s, the abstract expressionists dominated the postwar art scene and as a result, Manship’s work came to be seen as too traditional. However, his work received a reappraisal in the 1980s and is once again widely popular. Many visitors to the Nichols House Museum are admirers of Manship and are delighted to happen upon these two sculptures on view in our collection.

Laura Cunningham

Curator of Collections and Education

April 2020

[1] Thayer Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), 5.

[2] Ibid, 5.

[3] Thayer Tolles, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907),” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, accessed April 30, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/astg/hd_astg.htm

[4] Thayer Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), 11.

[5] Augustus Saint-Gaudens Papers. Rauner Special Collections Library Repository, Dartmouth College.

[6] Thayer Tolles, Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), 27.

[7] Ibid, 28.

[8] Alex L. Boylan, “Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the Erotics of Illness,” American Art 30, no. 2 (2016): 15.

[9] “Paul Manship.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. Accessed April 30, 2020. https://americanart.si.edu/artist/paul-manship-3096.

Paul Manship. Adam, 1922. Bronze. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.344.1-2.