Margaret Homer (Nichols) Shurcliff (1879-1959)

Margaret Nichols was the youngest child of Arthur and Elizabeth Nichols and she was doted upon by her older sisters who affectionally called her “chub.” Lively and athletic, Margaret enjoyed playing games and sports with the neighborhood children on Beacon Hill. In her memoir, Lively Days, she fondly recounted ice skating on a makeshift rink in the Curtis family backyard. Occasionally, her enthusiasm for life got the better of her, such as when she knocked herself unconscious from an ill-fated slide down the banister at 55 Mount Vernon Street.

Between kindergarten and age 13, Margaret attended Mrs. Shaw’s School at 8 Marlborough Street. The school was established by Pauline Agassiz Shaw, a philanthropist and suffragist who also founded the North Bennet Street School which offered vocational training to recent immigrants. Mrs. Shaw’s School was progressive for its time, teaching the genders equally and offering courses that female students were not traditionally taught. It also provided its students with manual training lessons in woodworking, pottery, sewing, weaving, and metalwork; a type of coursework that became increasingly common in Boston schools during the Arts and Crafts Movement. Although her work was “sometimes spoiled by haste,” Margaret Nichols excelled in her sloyd carpentry courses.

Sloyd, a Swedish manual training technique, embraced conceptual thinking, resourcefulness, and respect for hard work, and, like the Arts and Crafts Movement, aimed to combat the perceived deleterious effect nineteenth-century industrialization had on an individual’s sense of aesthetics and craftsmanship. Margaret’s sloyd education had a formative impact on her life and she maintained an interest in woodworking in adulthood.

In 1899, Margaret was rejected when she asked her mother if she could purchase her own turning lathe. A month later, undaunted, she enrolled in a carpentry and woodturning course at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; she had previously taken courses at MIT in chemistry and science. While MIT was not wholly unfamiliar with female students by this time, Margaret was the only female student in her carpentry class and the instructor, Professor Merrick, had to offer her his own dressing room upon the realization that there were no facilities for women in the entire building. When she missed a few classes to win several cups in the Longwood Tennis Tournament, Professor Merrick lamented to her that, “When you came regularly you kept ahead of the boys and they had to hustle to catch up, but now that they are ahead of you they don’t work so well.”

Margaret was a talented tennis player and she played to win. She was one of the first women to belong to the Longwood Cricket Club and she persuaded her parents to install a tennis court at the family’s summer home in Cornish, New Hampshire. In 1904 she won the Longwood tournament, defeating Evelyn Sears who would go on to win the 1907 U.S. Open women’s singles. In 1908, she and her doubles partner, Alfred Dabney, made headlines when they upset Eleanora Sears and Beals Wright who had been on a highly publicized winning streak in New York.

In addition to her love of carpentry and tennis, Margaret took after her father, Arthur Nichols, in her devotion to bellringing. Her first lesson was in 1900, and she soon became competent in both handbell ringing and tower-bell ringing. She and her father traveled to London in 1902 where the opportunities to learn were better. While there, she was featured in the English publication Bell News for successfully ringing a peal and the Ancient Society of College Youths listed her as the first woman to successfully ring a peal of “Stedman Triples.” When Arthur Nichols died in 1923, the only specific bequest in his will was his handbells, which went to Margaret. Margaret taught her children bellringing and began a longheld Christmas Eve tradition of bellringing carols on Beacon Hill.

In 1905, Margaret married the landscape architect Arthur Asahel Shurcliff. Although Arthur lived around the corner from the Nichols family on Beacon Hill, they formally met in 1901 at the Nichols family’s summer estate in Cornish, New Hampshire. Recounting their courtship, Arthur wrote, “It was there I met Margaret Nichols in a blue gown at her house, and later at the railroad station where she was whittling.” Shurcliff also loved carpentry and he followed the writings of Arts and Crafts theorist John Ruskin, encouraging Margaret to do the same.

Arthur and Margaret had six children: Sidney, Sarah, William, Jack, Elizabeth, and Alice. In 1912, the family relocated from 50 Mount Vernon Street to 66 Mount Vernon Street. In 1908, they built a summer home in Ipswich, Massachusetts and filled it with furniture and cabinetwork they made themselves. Arthur, fascinated by windmills, built one to power the house. At Ipswich, Margaret taught summer carpentry lessons to local children.

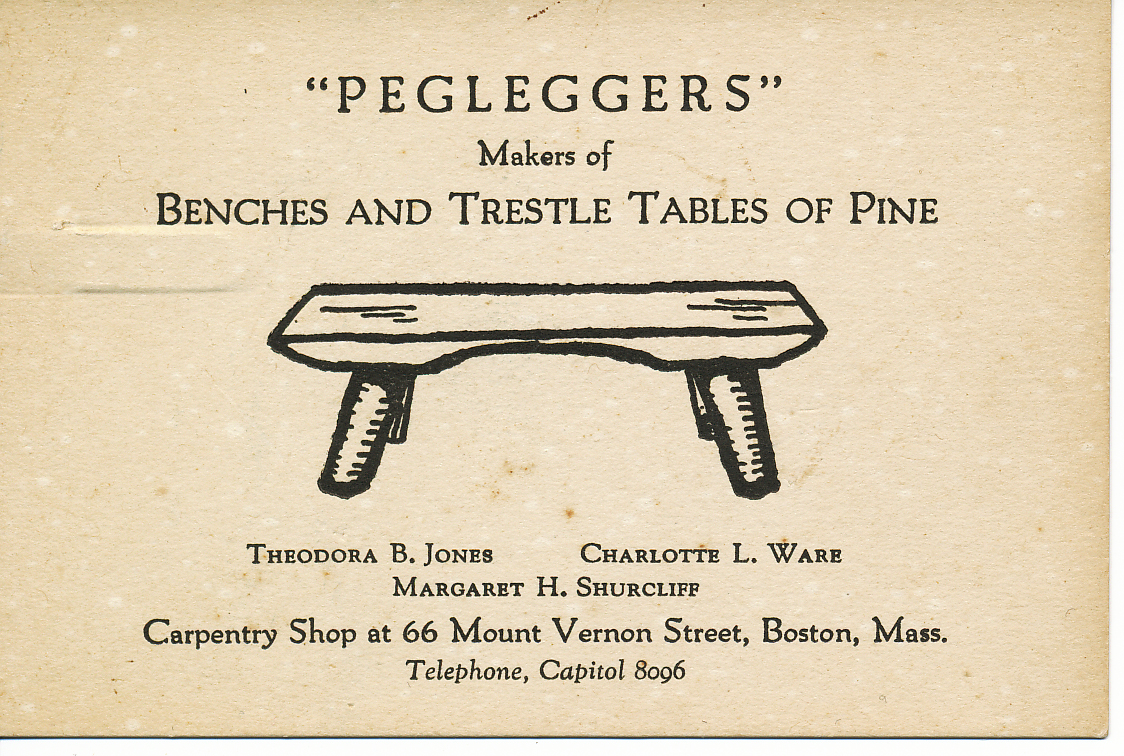

It was in the attic of 66 Mount Vernon Street that Margaret opened her business “Pegleggers: Makers of Benches and Trestle Tables of Pine” along with two other female carpenters, Charlotte L. Ware and Theodora B. Jones. Pegleggers produced colonial reproduction furniture using traditional hand tools, appealing to a Beacon Hill clientele that possessed an appreciation for the “authentic.” Like her sister Rose, Margaret embraced the Colonial Revival and its nostalgia for a mythic American past. In an interview for the Boston Sunday Advertiser, Margaret remarked that “in former days people made simple things with simple tools.”

In 1913, Margaret entered an essay contest issued by Pulitzer’s Magazine on the question of women’s suffrage. In her submission, she writes, “Even if the political field for women is small, it is important and why deprive the state of her service?” Like her sister Rose, Margaret Nichols was a member of the Women’s Peace Party and a committed pacifist during wartime.

In 1919, Margaret hosted a small group of people in her home to join American Civil Liberties Union founder Roger Baldwin in resisting a Red Scare government crackdown on anti-war dissenters, labor organizers, and immigrants known as the Palmer Raids. Referring to themselves as the League of Democratic Action, the group formed the nucleus of the Massachusetts ACLU. As a representative of the League, Margaret stood in solidarity with Lawrence, Massachusetts textile workers’ strike and she attended court hearings for Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, the most famous victims of the Red Scare. Margaret championed their cause and visited Sacco in Dedham prison on numerous occasions, bringing him craft materials to mitigate the inactivity forced upon him by incarceration.

Further Reading:

Welty, Emma. Makers’ Marks: Art, Craft, and the Fiber of Change. Edited by Emma Welty. Nichols House Museum: 2017. Download e-Catalog.

Margaret Nichols in her carpentery smock in Cornish, New Hampshire, ca. 1903. Original source unkown.

Margaret Nichols, ca. 1905. Original source unknown.

Margaret Nichols, ca. 1910. Nichols Family Photograph Collection, 1.42.

Pegleggers business card, ca. 1920.

Newspaper clipping, 1947. Original source unknown.